The first time I heard a pileated woodpecker, I thought that someone was using a jackhammer to bore through wood. Thanks to our built-in GPS system that can distinguish the difference in arrival rate, intensity, and frequency of sound, I was able to locate the origin of the drilling. About 500 feet away from me horizontally and 50 feet up, there was the source of the sound — a giant cartoon bird. It was Woody Woodpecker! He (Woody is male) was about a foot and a half high, had a red-tufted head, and a black body with white marking on the head and chest.

Woody’s sound – a low-pitched drumming — came in bursts lasting a couple of seconds. The individual blows were discernible and therefore, seemed to be countable, but alas, the rate was beyond the capacity of my brain. I have since learned that pileated woodpeckers can drill at the speed of twenty blows per second. I have also learned that the cartoon character Woody Woodpecker was indeed modeled on a pileated woodpecker.

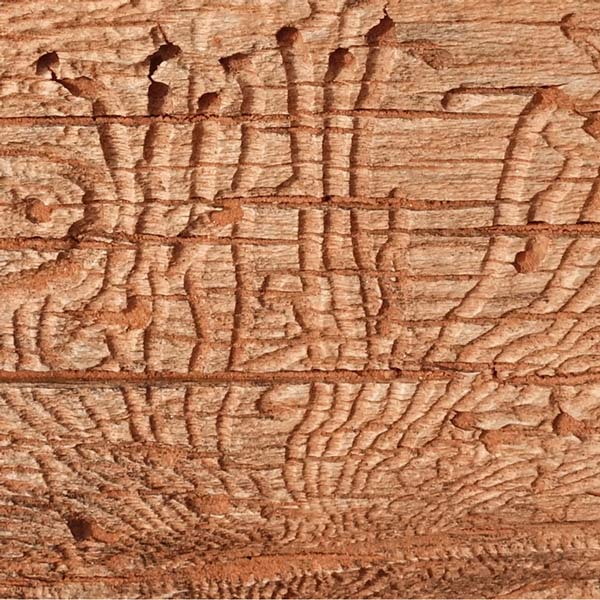

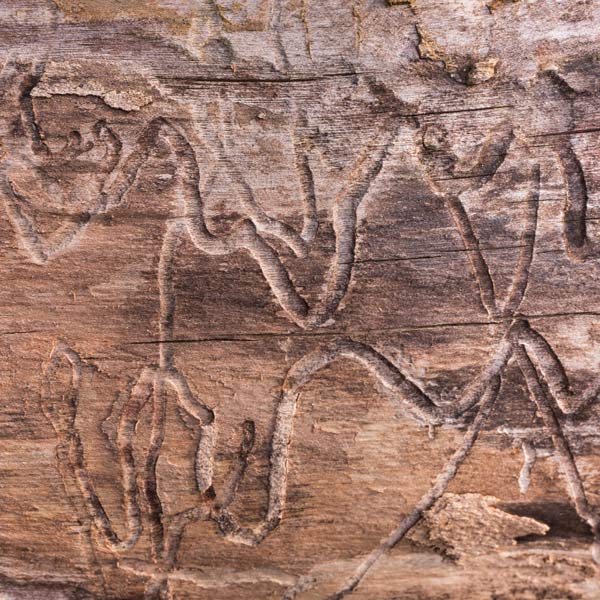

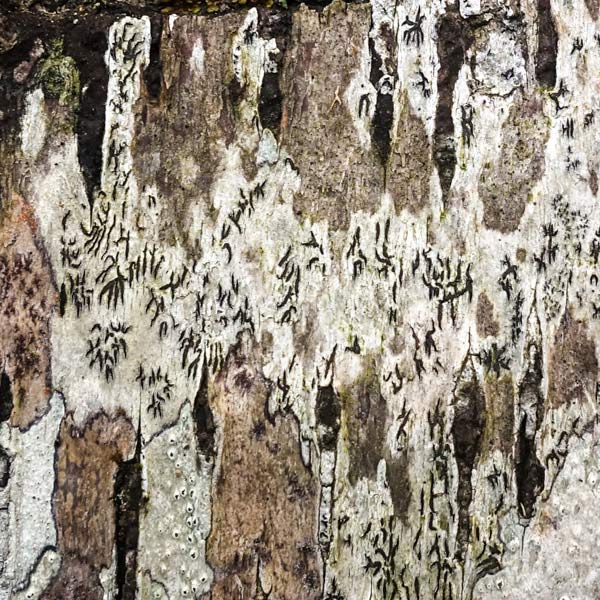

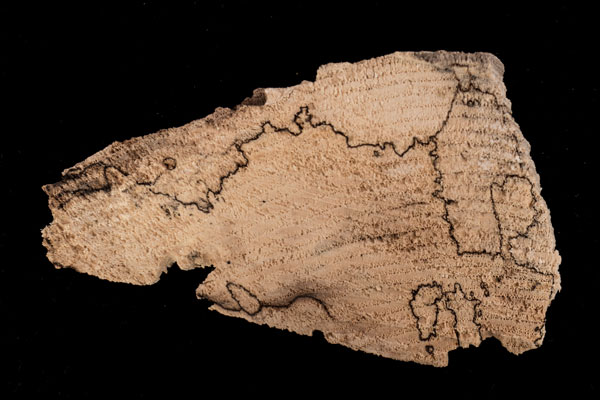

Pileated peckers drill for insects, but also to make living quarters for themselves, a mate, and offspring. The drumming sound establishes their territory and attracts prospective mates. It is April, mating season, and Westwoods is one big drumming circle. Along the Nature Trail off Dunk Rock Road, seven hardwood trees have been turned into multi-story apartments by whimsical feathered architects. The portals, usually vertical rectangles, are large enough to admit a pileated pecker’s portly frame and so numerous that I suspect these trees will be dead in a year. Woodpeckers abandon their homes after one use, but for many years to come, the discarded apartments will be occupied by squatters — other birds, raccoons, squirrels, and snakes.