The first time I heard a pileated woodpecker, I thought that someone was using a jackhammer to bore through wood. Thanks to our built-in GPS system that can distinguish the difference in arrival rate, intensity, and frequency of sound, I was able to locate the origin of the drilling. About 500 feet away from me horizontally and 50 feet up, there was the source of the sound — a giant cartoon bird. It was Woody Woodpecker! He (Woody is male) was about a foot and a half high, had a red-tufted head, and a black body with white marking on the head and chest.

Woody’s sound – a low-pitched drumming — came in bursts lasting a couple of seconds. The individual blows were discernible and therefore, seemed to be countable, but alas, the rate was beyond the capacity of my brain. I have since learned that pileated woodpeckers can drill at the speed of twenty blows per second. I have also learned that the cartoon character Woody Woodpecker was indeed modeled on a pileated woodpecker.

Pileated peckers drill for insects, but also to make living quarters for themselves, a mate, and offspring. The drumming sound establishes their territory and attracts prospective mates. It is April, mating season, and Westwoods is one big drumming circle. Along the Nature Trail off Dunk Rock Road, seven hardwood trees have been turned into multi-story apartments by whimsical feathered architects. The portals, usually vertical rectangles, are large enough to admit a pileated pecker’s portly frame and so numerous that I suspect these trees will be dead in a year. Woodpeckers abandon their homes after one use, but for many years to come, the discarded apartments will be occupied by squatters — other birds, raccoons, squirrels, and snakes.

This foot-long nest belongs to a colony of Bald-faced Hornets. The name Bald-faced Hornet is doubly misleading. First, the insect is actually a wasp, not a true hornet. Second, the adjective “bald-faced” suggests a lack of facial features, but “bald” is simply an unfortunate shortening of “piebald,” which means having a black and white design. Bald-faced hornets are aggressive, swarm, and can sting multiple times. They have been known to fly past several people to target the exact individual who disturbed their nest and to remember the attacker for up to a week.

The beautiful design of the nest belies the danger within. Its scallop-shaped layers are made of a pulp, which the wasps produced by combining organic matter with their saliva. This outer shell is up to twelve layers thick. Inside, tiers of hexagonal honeycomb once housed hundreds of wasps. I use the past tense because I came upon this nest in late September when the inhabitants were probably gone. The queen mother who started building the nest in the spring as well as the hundreds of sterile female workers she reared have all died. Only a few impregnated queen-hopefuls survive and they overwinter elsewhere and will start a new nest next year. But horrors! All summer, this nest had been dangling at waist-level (i.e. within reach of children) just a few feet from a very popular trail in Westwoods!

Ghost Plants (monotropa uniflora) have nearly translucent white stems with drooping, billowy caps that peek out of dark places in the undergrowth. They look like fungi, but actually belong to the blueberry family. Ghost plants pop up after a rainy spell just as fungi do. They actually feed off mycorrhizal fungi, an underground network of fungi that connects trees to one another and to other plants. The photosynthesis of trees sends carbon through the mycorrhizal fungi to the ghost plants.

The ghost plant’s shape accounts for its other common name, Indian Pipe. Inside the pipe’s chamber, there’s a beautiful yellow flower.

For more information on non-photosynthetic (heterotrophic) flowering plants, check out Tom Volk’s blog.

The Giant Leopard Moth is generally nocturnal, but I found it spending a lazy afternoon on the remains of an Eversource utility pole. It has iridescent blue legs and apparently a thorax to match, although it didn’t spread its wings to reveal that part of its body.

Two days later, I was startled by another monotone bug resting on the leaf of a bromeliad on my deck. The creature appeared to be staring at me with enormous black eyes outlined in white, but the “eyes” are protective markings to scare away predators.

It was indeed nerve-wracking getting in close to take a picture of this bug-eyed creature who appeared to be on high alert. Fortunately, the beetle didn’t perform the defensive trick responsible for the second half of his name, Eastern Eyed Click Beetle, else I might have dropped my camera. The beetle can lock its head, bend it backwards towards the thorax, then flick itself in the air. When it launches, it makes a clicking sound.

Oddly, the Giant Leopard Moth also has a talent for clicking! It can make clicking noises that are thought to interfere with the echolocation of bats, a main predator.

Mountain Laurel (kalmia latifolia) is the state flower of Connecticut (and Pennsylvania where I grew up). Indigenous to our area, it thrives throughout Westwoods.

In the winter, its twisted stems and dark leaves add a fairy-tale eeriness to what would otherwise be pretty upstanding set of forest plants. In late May and early June, the gnarly bushes might or might not bloom, depending on whether they are in full sun or shade or the severity of the winter. Last year, possibly because of a deep freeze in February, the leaves were mottled and only the bushes in full sun produced flowers. But this spring …. OMG, all of the Mountain Laurel, even the small specimens in total shade, are laden with clusters of pink and white flowers.

In 2000, another year of extraordinary Mountain Laurel flowers, Richard Jaynes, author of Kalmia: Mountain Laurel and Related Species credited the profusion of blooms to a mild winter (just like we had this year). But, he warned, after a year of profuse blooms, plants will focus their energy on the seed capsules, not the flowers.

This morning, I took a slightly different route from my house to Westwoods and stepped on something hard — not hard like a rock, more like round piece of wood. It was an orange-red shelf fungus (also known as bracket or conk).

Shelf fungi are a beautiful indications of rotting wood, usually growing horizontally around the base of trees. They are polypores, having tiny pores on their undersides rather than gills to distribute spores. This 6-inch specimen had been attached to a root of an oak tree stump by a stem (known as a stipe). It is the genus Ganoderma, translated as shiny skin and as far as I can tell, the species Curtisii. Its dark red topside and brown underside indicate that it is past its prime, or euphemistically “mature.”

I was surprised to learn that my conk is closely related to a medicinal tea in my pantry, which was left by my son during his last visit home. Depending on your source, Rieshi Mushroom tea has proven benefits in fighting infection, reducing certain tumors, and generally improving the immune system or it has no proven health benefits. It has, in fact, been used in asian medicine for hundreds of years and is a now a hot item in alternative medicine in the West.

When is a multi-ton boulder that has stood in place for the last 18,000 years considered erratic? If it was carried by a glacial far from its place of origin and dropped in an area where its composition is different than the surrounding native stone, geologists call the rock an “erratic” from the latin verb “errare,” meaning to wander.

Westwoods is riddled with large isolated boulders. However, most if not all have the same composition as the bedrock beneath them so technically, they are not erratics. Still, these mega-rocks were carried by monstrous glaciers from the last Ice Age and dropped helter-skelter wherever the physics of melting ice demanded, so their placement is definitely eccentric, whimsical, and capricious. Dare we say erratic?

For just a few days in the spring, male catkins —- slim clusters of drooping flowers (often crudely described as worm-like strands) drop from the forest canopy. Their female counterparts (usually chunkier and upright) remain in the tree, awaiting a good wind to impregnate them with the pollen from the males. Fertilized female catkins will produce seeds. In an oak tree, they bear acorns.

In Westwoods, the ground is strewn with male catkins from oaks and silver birch. They are extremely delicate so that any disturbance (such as picking one up to examine it) releases bright yellow pollen. The naked eye cannot see how gorgeous these flowers are but take a look at these enlarged scans!

When I submitted a photo of this bird corpse to the Merlin Id app, I learned that my bird, an adult male Blackburnian Warbler, is easy to identify and “a fan favorite.” “Flame orange throat” : check. “Triangular black cheek patch”: check. “Oddly shaped white wing patch”: check.

So how did this charismatic figure acquire such a formal moniker? Our bird was discovered pretty late in the naming process since he is a New World inhabitant. (He summers on the East Coast of North America and winters in South America.) Back in the 1700’s, one of his ancestors who had been living in New York or Connecticut was killed by a young Englishman named Ashton Blackburne, then stuffed and shipped to Ashton’s sister in England. Anna Blackburne, a self-taught naturalist, spent her days collecting and classifying insects from England and birds from her brother in New England. Anna was relatively unknown, but she shared her findings with the well-known naturalists of the day who would then publish her discoveries. (Grrr… another example of a woman working behind the scenes.) The Swedish botanist, Carl Linnaeus, honored Anna by naming this colorful bird after her. Ironically, the female Blackburnian Warbler is a “washed-out version of the male.”

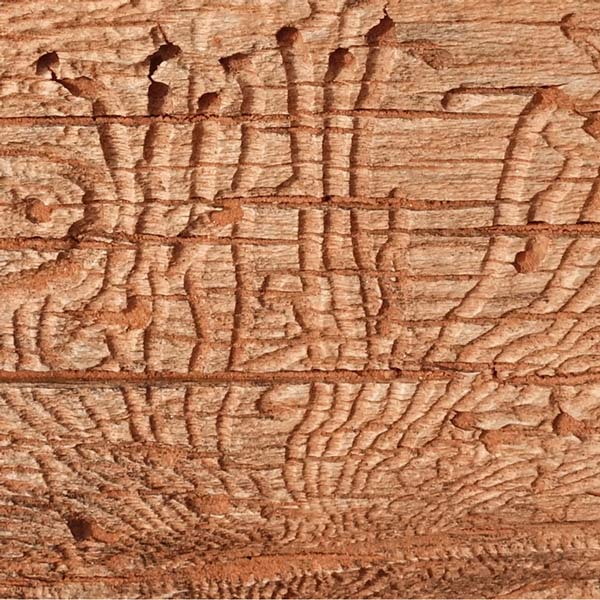

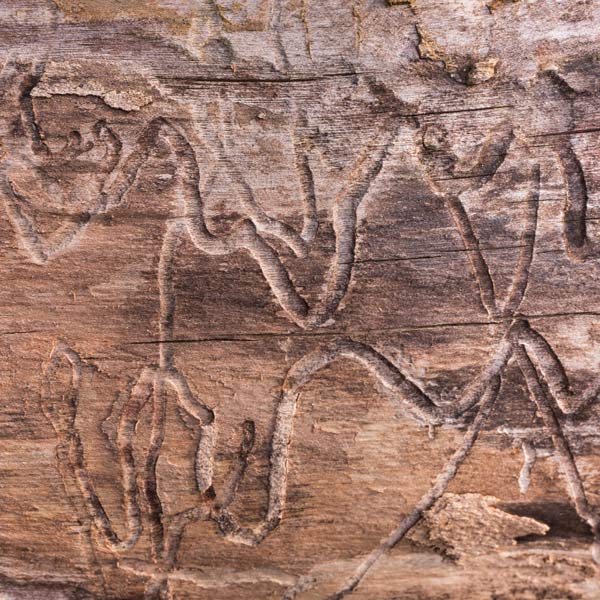

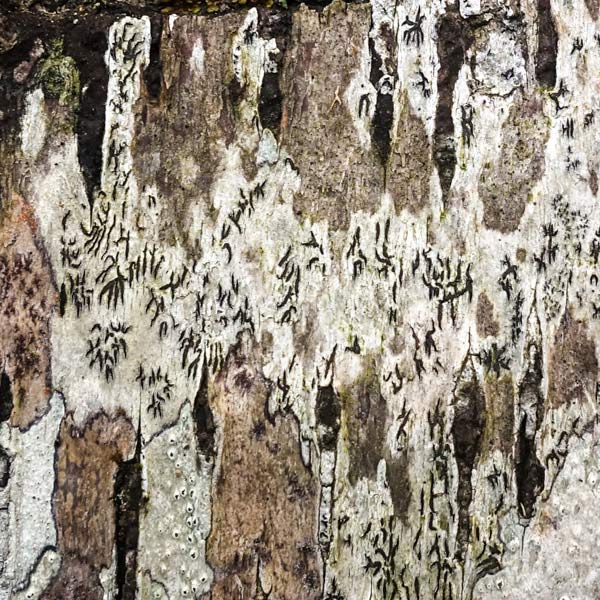

Rotting wood is my new passion. Where I walk in Westwoods has a greater share of dead trees than most other forest areas. It used to be dense with Hemlocks until they were killed by the wooly adelgid infestation. Now the forest floor is covered with downed trees and branches. It is truly a mess. I used to think it was ugly. But I started to see the standing stumps and logs as carved sculptures. Then I looked closely at some fallen logs and was mesmerized by the patterns. Some are made by fungi, some by boring beetles, and some by weather. Enjoy this gallery of rotting wood.

I knew of course that I was photographing a log, but when I saw the isolated details through my camera, I was mesmerized by an abstract world of shapes and colors. Looking at the image afterwards, however, I began to see the white blobs as central characters. Then the characters became animals. Finally, one of the animals kissed the other.

I now know that the kissing blobs are a form of crustose lichen. Crustose lichens, as their name implies, form crust-like structures – in this case, on a rotting log. All lichens are made up of algae or bacteria (the plant part that provides the photosynthesis) and fungi (the part) that provides structure. The black outline of these blobs — a painterly effect of nature — is due to the wearing away of top structural layers, exposing the underlying threads (hyphae) that attach the lichen to the log. Learning the science of the image didn’t spoil it for me. It’s semi-abstract quality was sealed with the kiss.

I found this amazing structure on the ground near my house. Its former inhabitants — paper wasps – had probably been living right under my nose all year in this attached unit under my porch. I counted 225 hexagonal rooms – a major hotel! The hotel is shaped like an umbrella (we are seeing the underside in the picture) with a roof constructed with layers of homemade paper — organic matter that the wasps harvested, then mixed with their saliva, and formed into sheets.

Now, with temperatures in the teens, the wasps are either dead or hiding in crevises or inside my house. Unless there was an unusually plentiful food supply and easy access to warm quarters, the worker wasps would have sacrificed food and shelter (in other words, their lives) for their Queen. When the Queen reemerges, she will discover that her nest is gone. But, if she liked the location (and I hope she did), her offspring will build in the same place. So I’ll be looking out for another creative addition to our house in the spring of 2022.

These rocks seem to be soaring through space. Their meteoric rise to fame happened overnight. Before the freeze, they were just ordinary pebbles indistinguishable from their neighbors. But while we humans slept, these particular rocks, lying in a slow-moving area of a stream bed, were cast in a dramatic production of ice crystals.

Hopefully this lovely Eastern Tiger Swallowtail had achieved the ripe old age of about two weeks and had therefore lived a full life, for it couldn’t possibly survive much longer. I found it in the middle of the trail. Both hindwings were missing and its right forewing was damaged. Normally, in the presence of a person, a butterfly would fly away, but this one hopped. Its left forewing, still intact and operable, fluttered with each attempted takeoff so that the butterfly lifted a few centimeters on the jumps. When it was safely off the path and in the leaf mulch, I walked away with a pang in my chest – a familiar and necessary reminder of death that is one of the many offerings of walking in a forest.

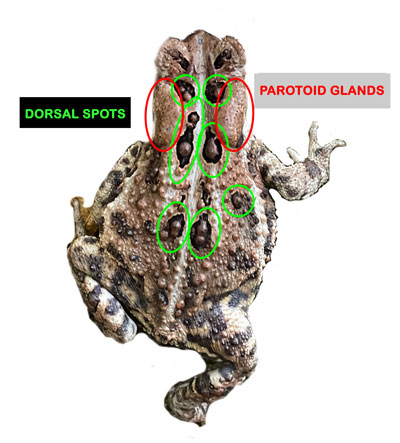

I’ve seen plenty of toads as they were hopping away to escape my foot. But this toad froze in its tracks. As I bent down to take its picture, I experienced a mixture of shock, disgust, and concern, for it appeared to have holes in its back, each filled with brown seeds.

That evening, I settled into my comfy armchair to read about toad anatomy. The holes in its back are called dorsal blotches or spots and the “seeds” are actually warts. Toad identification includes counting how many warts are in the spots. One or two per spot and it’s an American Toad. More warts per blotch, then it might be a Fowler Toad. Interbreeding is common between the two species, which probably explains why our toad has one or two warts in most of its spots, but one spot appears to be crowded with maybe five warts. So this is probably not a purebred American Toad (a Yankee?) but one with a bit of Fowler in its past.

The two oval sacs behind the eyes are the parotoid glands that secrete bufotoxin, a substance that ranges from mildly irritating to poisonous, depending on the species. The American Toad’s protective secretion is on the mild side, a fact that for most people is reassurance that their curious dog may vomit, but probably won’t die. But for others, it’s a matter of self-interest, for toad-licking is making a comeback!

Toad-licking is a real thing, but most toad abusers these days milk the glands and then dehydrate the bufotoxin so that it forms a powder that is suitable for smoking. Apparently, the most satisfying hallucinogen comes from the Colorado River Toad. Symptoms of ingesting toad serum include unresponsiveness or having convulsions or vomiting. Yet so many toad users report having a religious experience (“being one with God”) as well as enduring positive feelings that Johns Hopkins University is researching the use of toad venom to treat depression.

Like all good experiences, getting high from smoking toad serum has been overdone. Advice from an addiction center website: If you or someone you know is abusing Toad Venom, there is help available.

This bright orange mushroom is so named because it tastes like chicken. You would think that it’s similar to another more commonly known edible mushroom, Hen of the Woods, but the two fungi named after a female fowl are only distant cousins. After watching an informative video by the same upbeat mushroom aficionado who taught me about Turkey Tail, I was able to check all the boxes for laetiporus sulphureus. Chicken of the Woods grows in layers on dead trees. It is velvety, thick, and fibrous. Its topside is orange with delicate yellow edges, and importantly for its identification, its underside is yellow with microscopic pores. I scanned a sample and enlarged it by a factor of 20 in order to be sure of those pores.

I once vowed that I would never forage mushrooms, but I felt confident enough to harvest a chunk of the alluring fungus, sauté it according to the Chicken of the Woods recipe by the Sophisticated Caveman, and eat it. It was delicious! And indeed tastes like chicken.

(If there are any blog posts following this one, you will know that I survived.)

Just before leaving for a three-week vacation, I took some photos of a fungus covering a fallen dead hardwood tree. While I was in California, I watched a video by a charismatic fungal enthusiastic, Adam Haritan, who made it clear that my fungus was either Turkey Tail or a Turkey Tail look-alike and that the only way to know for sure would be to examine its underside.

If the underside was white and had tiny pores, my fungus was trametes versicolor, commonly known as “Turkey Tail.” If it was more beige and smooth, it was stereum ostrea with the pitiable moniker “False Turkey Tail.” If it was slightly purple and had a toothy structure, it was trichaptum biforme – “Violet Toothed Polypore.”

During the three weeks, I realized two things: 1) that I was subconsciously rooting for my fungus to be what mycologists call true Turkey Tail and 2) how prejudiced I was being. After all, “False Turkey Tail” was so-named only because of its resemblance to the topside of trametes versicolor, not because it had some nefarious motives as an imposter. And besides, Turkey Tail itself was named because of its resemblance to an actual turkey’s tail. And the poor Violet Toothed Polypore, which is in fact the most common of the three species, had the role of a third child, mentioned for its relationship to the other two.

When I arrived home, I headed to the log in question, picked off a piece of the overlapping fungus and flipped it over. It was clearly violet and toothy. As I celebrated the identification of Violet Toothed Polypore, I felt a tinge of disappoinment in myself for feeling a tinge of disappointment that it was not true Turkey Tail.

This bright yellow fungus (calocera cornea if you care to know), commonly known as Small Stagshorn, is a petite relative of Yellow Stagshorn. It grows on rotting stumps and buried roots, quickening their decay. In a forest of greens, browns, and greys, its yellow spires scream out for attention. “Look at me!” When I first spotted a clump in a muddy bog, it seemed so audacious that I was immediately suspicious of its motives and didn’t dare to even touch it. Reading about it later, I learned that Stagshorn is in fact edible in the sense of being “non-toxic,” although it is both bland and gooey so that it is generally used only as a garnish. Even if it were described as being delicious, I would never dare to actually ingest it in case I was wrong in the classification, although I did go back to touch it. Who could resist when the various adjectives used to describe it read like an entry in Roget’s Thesaurus –- waxy, slimy, sticky, gelatinous, jelly-like, and viscous. Personally, I found it to be slightly icky.

In the 1980’s, almost all of the Eastern Hemlocks in Westwoods died from the Woolley Adelgid disease, leaving what appear to be medieval weapons strewn about on the forest floor. These bludgeons are Hemlock branches with tapering concentric rings on the insertion end. When the branches are still attached to the mother bole, they remind me of sculptures.

Why do they taper like this? I asked my go-to tree person, David Zuckerman, who is a Horticulture Manager at the Washington Park Arboretum in Seattle and also my brother-in-law (read David’s blog about Hobbit Trees). This extra wood, called a collar, is laid down by the trunk to give the branches more support. David sent me a research paper by Alex Shigo, who is known in some circles as the “father of modern arboriculture.” Shigo’s diagrams indicate that Hemlock branches have thicker collars than most other species due to having a core of hard resin.

I’ve been spending these late April mornings moving pachysandra to fill in worn spots where my dog lays after walks. I was about to drive my shovel into the earth, when I noticed –-and swerved just in time to avoid impaling –-a bird. I have handled dead birds before and every time, I am pained by their weight. The sensation of their little bodies in my hand is paradoxically weighty as if I can suddenly measure in tenths of an ounce.

Unsolicited dead birds remind me to take time out to appreciate nature. To memorialize them, I place them on my Epson V700 to scan them in at some ridiculously high resolution so that I can view an enlarged image of their feather patterns up close.

Normally, I’m not interested in their identity, just in their birdness. But thanks to my new bird identification app, Merlin, I learned that my guy is a Black and White Warbler (a guy because he has black cheeks). He comes from a family of tree foragers, good at picking out insects from the grooves of bark. But unlike some of his cousins such as the Brown Creeper, who starts at the bottom and forages upward, or the Nuthatch, who hops downward, my bird is quite talented and hops every which way.

Ugh, I’m getting attached, but it’s time for the final step in my bird appreciation routine. To pick up his floppy, rotund body and hurl it into the woods.

Symplocarpus Foetidus: smelly fruits

It’s March and there are hundreds of baby skunk cabbages in the creek along the Blue Trail. The “baby” is actually a reddish purple or mottled yellow shell (the spathe) that holds a cluster of flowers attached to a spike (the spadix). The spathes are miraculous little space heaters that keep the prenatal buds between 60° and 70° and as a side-effect, can melt snow or ice. This thermogenesis is accomplished by metabolizing starch that had been stored in the roots over the winter. A few weeks ago, several of these pointy gnomes were peeking through the snow.

Next to the purple shell, there’s what appears to be a second spathe that’s green, though it’s actually a curl of green leaves. These will unfurl to be a large stinky adult skunk cabbage. The plants have evolved to smell like dead animals to attract early garbage-loving pollinators such as some flies and beetles while repelling early forest carnivores such as deer and rabbit. The fetid odor is actually a good thing for us humans, since the leafy greens look good enough to eat, but would in fact make a poisonous salad.

Here in the Northeast, many of us experience a strong feeling of protest, an internal voice that shouts “No!” when the deciduous trees are about to lose their last leaves.But some leafy trees do keep their leaves until spring! There’s even a special word to describe this tenacious holding onto living plant material through the winter — marcescence.

I never appreciated the tan papery leaves on Beech and Oak trees that flutter throughout the winter because I assumed they were a sign that the trees were dead. One year, it dawned on me that the parched leaves appeared year after yearon the same trees. They had to fall off at some point to allow for the new leaves, but when? I watched as they held on through heavy snowfall, frost, ice storms, and gusty winds. It was February, then March, then April… suddenly there were new green leaves; I had missed the transition!

This winter, take note of marcescent trees, whose leaves make a crinkly sound in the wind, glow when backlit by sunlight, and add color to the forest (even tan stands out in winter).

These mysterious objects that look like desiccated golf balls were originally destined to be oak leaves but ended up housing wasp larvae. They are apple galls, a gall being any abnormal growth on a tree and the apple part because young ones resemble green apples.

In early spring, an “oak apple wasp” injects an egg into a leaf bud as well as chemical instructions that co-opt the bud into forming a cocoon for wasp larvae. In summer, a mature wasp emerges through a tiny escape hole.

Like many of nature’s most creative inventions, galls have a bad rap. However, oak galls do not harm the oaks. They provide food for birds and when pulverized, can be used to make an ink that was the medium of medieval scribes. The Constitution and the Declaration of Independence were written in oak gall ink!

I occasionally come across fallen birch twigs that are a shocking blue-green color. Fellow hikers have had the same reaction that I had — that the color does not look natural ; someone must have dyed the wood.

When Museum curators saw that same hue in artwork by Italian furniture makers working in intarsia –- elaborate designs made with inlaid wood –- they too thought that the wood was dyed. However, scientific analysis of the artwork showed that the blue-green wood is an example of spalting – the coloring of wood by a fungus, in this case, the elf-cup Chlorociboria aeruginascens. Fifteenth and sixteenth century artists used the green wood to depict grass, leaves, bird feathers, animal eyes, and luxurious clothing. Back then, chlorociboria-infested wood was as valuable as precious metals.

This white-tailed deer might have been taken down by a coyote or died a natural death.

Although the skull is damaged, the zig-zag markings on the top are beautifully intact. Similar to spalting, which is a network of lines marking fungal boundaries in wood, these cranial sutures mark boundaries between bones.

When the deer was young, the sutures were fibrous areas that allowed the bones to expand. They also indicate stresses placed on the skull by chewing. In male deer, the largest sutures (the coronal pair that meander horizontally across the top of the skull) indicate the presence of antlers. The smaller wiggly line in the back of the skull is the lambdoid, and the vertical one extended towards the mouth is the sagittal suture.